Published in the February 22, 2018 edition

By MICHAEL GEOFFRION SCANNELL

NORTH READING — Last Thursday, Eric Evans gave a riveting presentation entitled “North Reading B-17 Crash Declassified: Secrets Revealed.”

The event was presented jointly by the North Reading Historical Society and the Flint Memorial Library where a standing room only crowd filled the library’s the activity room to capacity.

Evans, a financial advisor with Edward Jones, started off his talk by saying he was not a historian but loved history. He said he had been influenced by his father’s interest in plane crashes and their causes. He went on to explain how he had seen a news story about a B-25 bomber that struck the Empire State Building in July of 1945 on its way to Newark Airport. In looking into that crash he came across information about the mysterious crash of the plane known as the Flying Fortress in 1942 here in North Reading.

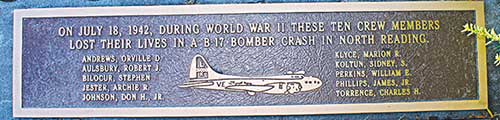

NORTH READING honored the 10 crew members who lost their lives in the B-17 bomber crash in town on July 18, 1942 by including this bronze plaque on the memorial marker on the town common reserved for other wars and events spanning the French-Indian War to the Persian Gulf War.

(Maureen Doherty Photo)

He showed the audience photographs and diagrams of the interior and exterior of various B-17s to illustrate the location and jobs of the 10-member crew. He also showed his audience combat footage of the B-17 in action. Once all the background information had been provided, Evans was able to move on to the incident here in town.

Shortly after 3 p.m. on July 18, 1942, one eyewitness, 16-year-old Leonard “Gig” Stephens, heard the sound of an aircraft in trouble from his home near the Red Hill Country Club, now known as the Hillview Country Club, and ran outside where he saw a B-17 Flying Fortress bomber descending.

The plane crashed in a wooded area behind what is now School Hill Lane in North Reading on an unusually foggy day that made visibility difficult for the pilots. The aircraft took out at least one house chimney on the way down, crashing deep in the woods parallel to where the Middle School stands now. All 10 – Orville Andrews, Robert Aulsbury, Stephen Bilocur, Archie Jester, Don H. Johnson Jr., Marion Klyce, Sidney Koltun, William Perkins, James Phillips Jr. and Charles Torrence – were killed.

Miraculously, no one on the ground was injured or killed. There were also witness accounts that the airmen were firing their machine guns prior to the crash presumably as a means to warn civilians on the ground of the impending crash. There is also a theory that the pilots may have been looking for a small grass airstrip near Route 28 that was then known as the North Reading airport, Evans said. During WWII, North Reading was still quite a rural community of mainly farmland and woodland.

Evans’ presentation included an article from the July 27, 1989 edition of the North Reading Transcript showing a 1942 newspaper photograph of townspeople gathered at the edge of the woods near the crash site that had been condoned off by State Police and the military. Residents of the town also set up an impromptu canteen area on a large flat rock near the crash site where they left sandwiches and coffee for the investigators.

There was another slide of the original military crash report, which stated that a phenomenon called “flutter” may have caused one of the airplane’s wings to literally fall off on its descent. Further supporting this theory was the fact that an undamaged wing was found a significant distance away from the wreckage, according to Evans.

Despite conflicting accounts of the origin of the flight and its intended destination, Evans’ presentation made it clear that the trip began in Gander, Newfoundland where a U.S. airbase had been established before the U.S. had entered WWII. This airbase was established because its location made it the shortest distance for planes to cross the Atlantic from North America to England.

The plane was part of the 29th Bombardment Squadron and was headed to the Johnsonville Naval Air Development Center in a suburb of Philadelphia. Because this B-17 was part of the very first production runs of this bomber plane, by 1942 it needed to be retrofitted with the latest armaments, Evans said.

Norden bombsight

One of the reasons that much of this information was kept secret for so long was that the plane carried the highly top-secret Norden bombsight, which was found by investigators relatively quickly on the day of the crash. The U.S. Army Air Corps was attempting to keep this classified information out of the hands of the Germans.

Upon news of the crash the Massachusetts State Police cordoned off the crash area, Evans said. State Police were then dispatched to retrieve the Norden bombsight and secure it until military authorities could pick it up. The bombsight contained an explosive charge; in the event of a crash it was literally supposed to self-destruct so the enemy could not gain this technology. However, the bombsight was found intact.

Carl Norden was a Swiss engineer and inventor who, using gyroscopes and other devices, built what Evans called “an analog computer that uses the plane’s airspeed, altitude and visual sighting of the target to tell the bombardier exactly when to drop his payload.” Norden bragged that using his bombsight he could “drop a bomb in a pickle barrel from 20,000 feet.”

According to Evans, experts now believe the bombsight was probably only about 10 percent effective, but during the war the bombsight technology was highly classified. In the 1930s when Norden was developing the bombsight, however, he was very enamored with the work of German engineers and hired many of them to work on the project. Ironically one of his assistants had sold the plans in 1938 to the Germans, unbeknownst to the U.S. military.

Afters Evans completed his presentation, audience members surrounded him, eager to ask additional questions about the crash and relay to him various stories about it that they had heard over the years, either firsthand or as told to them by family members.