Prom king, sports star, best Dad

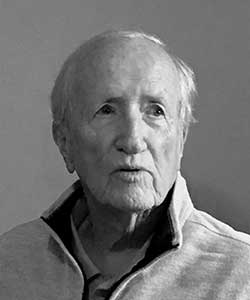

WAKEFIELD — Richard A. “Hoop” Henshaw, 91, of Wakefield, died on Dec. 5, 2024 at Life Care Center of Stoneham, of Alzheimer’s Disease. A fall and injured arm kept him from his home for 12 days, the first time he had been hospitalized in over 10 years.

WAKEFIELD — Richard A. “Hoop” Henshaw, 91, of Wakefield, died on Dec. 5, 2024 at Life Care Center of Stoneham, of Alzheimer’s Disease. A fall and injured arm kept him from his home for 12 days, the first time he had been hospitalized in over 10 years.

He was born at home in Somerville, and was the only child of Llewellyn J. and Freda P. (Burns) Henshaw, on Jan. 22, 1933. His parents were naturalized citizens from Nova Scotia, he from Bear River, she from Sandy Cove.

Growing up, he did not seem to have been aware of the Depression. His father never lost his job, and the little family did not struggle. They lived in a three-story walkup, occupying the middle floor. Hoop described one of his early chores was to empty the pan of water from the melted ice underneath the ice box; when he forgot, the family woke up to a soggy slog through the kitchen at breakfast.

When he was in elementary school, he contracted scarlet fever, which was serious in the days before antibiotics; the death rate for children was 20 percent. A quarantine sign appeared on the family’s door, and Hoop was confined to a bedroom for an entire month; he missed enough school to be held back a year.

One of the hallmarks of Alzheimer’s Disease is that sufferers often can’t remember how to use a toothbrush, but they can describe in vivid detail the events of their childhood. Hoop recalled the miserable month of quarantine frequently; he also recalled foraging in the Somerville dump with his pals, looking for deposit bottles and other treasures; taking free rides on the backs of the electric trolleys, and running when the driver stopped the car; stealing fruit from unguarded trees, and playing endless games. He cherished his Red Ryder BB gun and still has it.

He and his mother spent many summers in Nova Scotia with her parents, boarding the S.S. Evangeline in Boston and landing in Yarmouth, Nova Scotia. From there, a long dusty bus ride over dirt roads to Sandy Cove, and the home of schooner Capt. Billy Burns and his wife Caddy. Lew would join them for his two-week vacation. Hoop had no playmates, but was free to explore, usually followed by Candy, a cocker spaniel who was a welcome sidekick.

Back home in Somerville, Hoop exhibited signs of his natural athletic ability in all sports.

He played one season of football, when he was a student at Northeastern Junior High. “I was an offensive and defensive end. Caught the winning pass to win the city tournament. But I didn’t like it. It was too rough. I got the (stuffing) kicked out of me.”

At Somerville High School, he was a standout athlete in both baseball and basketball, and played on winning teams. In baseball, he played at Fenway Park, and hit a double to win the game against Mission High. He played at Braves Field, when Somerville won the state championship.

He dribbled a basketball on the parquet floor of the Boston Garden, where Somerville was runner-up in the Tech Tourney.

Summers he played for American Legion Post 19; the team came within one game of competing for the national title in 1951, but were beaten by Bristol, Rhode Island.

After high school graduation in 1952, he enlisted in the Army and was a member of the Military Police. He was not sent to Korea, but served his two years stateside. He played basketball on the Battalion Basketball Team at Camp Gordon, Georgia, where he met Hal Kerrigan of Woburn, and made a friend for life. When he mustered out, he had achieved the rank of corporal.

He enrolled at Northeastern University, majoring in Business Administration, enjoying the benefits of the G.I. Bill. There were only four buildings on the NU campus in 1955, and tuition was $350. Hoop commuted from Woburn, had to study hard, and so he had no time for basketball. He graduated in 1959.

He took up golf instead. Curiously this right-handed batter was a left-handed golfer. Soon he was a very good golfer, and won trophies and merchandise; he was a popular member of the Woburn Country Club. It took him 20 years, but he made his first hole-in-one in 1975.

He became a sales representative first for Sexton Can of Everett, and later for Gil Sullivan and I-PAK, Independent Packaging of Quincy, where he worked for 28 years, retiring at age 70. He served one term as president of the New England Coatings Association.

In 1958, Hoop’s mother died of leukemia. They were very close; this was a huge loss for him. Two years later, his father married Emilie P. Roach; Hoop gained both a mother and a sister, Carol Roach, 17. Carol had been an only child until then, and always wanted a sibling; Hoop had been a “lonely only” himself, and was happy to have a sister. When he couldn’t golf on a Sunday, he would accompany Carol to church. Years later, when Carol and her husband had a little boy, young Sandy was spoiled by ”Unca Dick.”

In his late thirties, Hoop (then called Dick) was introduced to Kristen Kingsbury, a farm girl from Martha’s Vineyard at a Boston watering hole. She was not aware that her friends decided to play matchmaker. When it was closing time, they locked her out of their car and drove off. Dick was forced to drive her home to her Back Bay apartment. She made him a cup of terrible instant coffee. Her cat stared at him from the bookcase, he stared at the door, and left in ill-disguised haste.

She thought she’d never see him again.

They were married at the Woburn Country Club (his choice) in 1975.

They moved to Wakefield in 1977 with their cat Shelmerdeen-Mao (who had gotten used to Hoop). The cat never got used to the two children, however, and stayed a room away from them at all times. Craig Kingsbury and Elizabeth Burns, were, like their father, born at home.

Hoop earned his stripes as a father; he was a mellow and patient parent. He did not grow up with pets, but didn’t object to a succession of hamsters, guinea pigs, rats, more cats, and an iguana who kept growing and requiring larger cages. He drove the kids and their friends endless miles to ski, hang out at the mall, go to games. He didn’t mind when they took over the dining room with Girl Scout meetings, mural projects, pinata construction parties and the like. He didn’t try to be the “cool Dad,” he just was one. Very little rattled him, except the day the iguana escaped and he discovered that “Pebbles” was not mellow.

He had Alzheimer’s much longer than anyone realized. Even his primary care physician, surprised at the diagnosis, said, “He presents so well.” After giving up his driver’s license — and not without a fight — Hoop’s world got smaller. It was small, but rich in love. Fellow congregants at the Unitarian-Universalist Church, neighbors, Bob the letter carrier, a series of paper boys, and all visitors to the house would engage with Hoop on matters only he understood; they all earn their “starry crowns” for their patience and good humor.

For his 90th birthday, when COVID prohibited a gathering, his children and their friends, Internet-savvy fans of the soon-to-be nonagenarian, sent out an appeal. Every day, another fistful of cards and letters came from everywhere. He received 142 cards in all, and kept the decorated box filled with them on a table next to his side of the kitchen table.

Granddaughters Esme and Juniper, who live across the street from “Papa Hoo,” could be relied upon to keep the old basketball star’s skills well-honed with spirited games of “Free Throw.” Horse chestnuts and a small kitchen pail showed them that the old man’s eye-hand coordination had not been diminished, and Hoop had earned his nickname.

Isla, the girls’ black Labrador, in baseball tradition, stayed close by Hoop’s chair at every gathering where food was a feature, kn