Published in the September 28, 2015 edition.

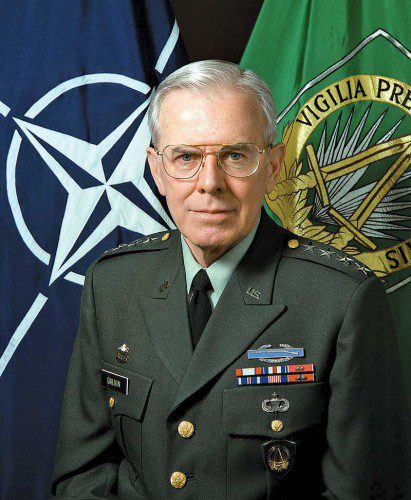

WAKEFIELD — John Rogers Galvin, 86, the son of a Wakefield mason who retired as a four star U.S. Army General, died in Georgia Friday, Sept. 25.

Flags all over Wakefield were flown at half mast in honor of the general, after whom Wakefield’s middle school is named.

Burial will be in Arlington National Cemetery at a later date. No further obituary information was available at press time.

“Jack” Galvin, born in 1929, grew up on Pleasant Street, the son of well-known mason John J. Galvin and wife Josephine. The future U.S. Army Gen. Galvin attended the West Ward and Lincoln schools. In a Wakefield Item column from 1968, he is described as having been a hod carrier as a young man, meaning he helped lug bricks for his father.

The general and others in the Wakefield High Class of 1947 were born the year of the great stock market crash and grew up during the Depression.

In a Veterans’ Day ceremony 20 years ago, the general recalled watching in awe as old soldiers dressed in still-fitting uniforms marched in the town’s various parades. Jack was just a boy and some of those he marveled at were Civil War veterans.

The future general attended Merrimack College briefly. At 19, he joined the 182nd Infantry, Massachusetts National Guard., the Army’s oldest unit and descendant of the Minutemen. In December 1949, Massachusetts Governor Dever nominated Galvin from the enlisted men of the state National Guard to take the entrance exam to the military academy at West Point. In June 1950 he received orders to report to West Point on July 5.

In his first year at West Point, Jack Galvin was a serious student who also used his wit, ability and understanding as a cartoonist for The Pointer, the academy’s official magazine.

In 1954, Jack graduated West Point as a second lieutenant of the infantry. His career quickly took off. He completed Ranger and Airborne schooling and for a year was a rifle platoon leader in Puerto Rico. He was sent to the Colombian Andes as a Ranger adviser, returning in 1958 to the 501st Airborne Battle Group, 101st Airborne Division, at Fort Campbell, Ky. There he was in command of the “D” and later “A” companies.

in 1960, Galvin attended the Armor Officer Advanced Course at Fort Knox. Upon graduation he married Virginia Lee Brennan.

After a year of graduate studies at Columbia University, he received a master’s degree in History and an assignment to West Point as an English instructor. Following this tour he attended the Command and General Staff College at Fort Leavenworth, Kan. As part of the Master of Military Science Program, Galvin wrote the important book “The Minute Men,” a study of the opening battles of the American Revolution.

From 1966 to 1970, he served two years in Vietnam, mostly in the First Cavalry Division, where he commanded the First Battalion, Eighth Cavalry during the Cambodia incursion, receiving the Silver Star and Distinguished Flying Cross. In the interim he was a military assistant to Secretary of the Army Stanley Resor. He also wrote “Air Assault,” on the development of air mobility.

After a staff assignment in Combat Developments Command, he attended the Fletcher School of Law and Diplomacy at Tufts University in the Army War College Research Fellowship Program. During this year, he wrote “Three Men of Boston,” a political study of the events leading up to the first battle of the American Revolution.

Assigned to Europe, he served as military assistant to Generals Andrew Goodpaster and Alexander Haig at Supreme Headquarters, Allied Powers Europe in Belgium, then as Commander, Division Support Command and later Chief of Staff, Third Infantry Division (Mechanized) in Wirzburg, Germany.

He was promoted to Brigadier General in 1978 and became Assistant Division Commander, Eighth Infantry Division (Mechanized), Mainz.

In the summer of 1980, after seven years in Europe during the on-going Cold War, he was reassigned to the Training and Doctrine Command, Fort Monroe, Va., as Assistant Deputy Chief of Staff for Training. He was promoted to Major General in May 1981 and assumed command of the 24th Infantry Division (Mechanized), Fort Stewart, Ga., on June 1, 1981.

In the mid-1980s, General Galvin was commander of all U.S. forces in Central America, continuing his rise through the upper ranks of the military. In February 1987, after some months of conjecture, he was named Supreme Allied Commander in Europe as the Cold War began to thaw. Before his appointment to command NATO, the general told the Daily Item, “At this point it’s (NATO’s move), just a rumor. There are a lot of changes coming in the high command next spring. I’m a soldier and I will go where they tell me to go.”

Galvin succeeded General Bernard Rogers in June of that year. Also in 1987, he was named “Person of the Year by the national Association of the United States Army. General Galvin, as Supreme Allied Commander Europe, was charged with the security of Western Europe. He and his wife moved to Brussels, Belgium.

In his NATO post, the general saw the Berlin Wall fall and also had to deal with rising ethnic tensions in Yugoslavia and in the Persian Gulf. The general’s cousin, Town Clerk Mary K. Galvin, and others visited while he was serving as SACEUR and were amazed at how the trappings of his office never seemed to change the man they had known all their lives.

During a WCAT program taping in July 1991 with area reporters, the general had to excuse himself to call then Chairman of the Joint Chiefs of Staff Colin Powell about the situation is eastern Europe. In that interview, conducted to coincide with Galvin being named grand marshal of the reformed Wakefield Independence Day parade, he remained as humble as ever.

The general said values he learned growing up in Wakefield helped him move up through the various ranks of the military.

“When rank is added you have to broaden your horizons and be more capable. You just can’t stand and bark orders. … The basis of my success is the ability to articulate. Teachers like Bernice Caswell (Wakefield High English instructor) gave that to me. I felt special after going through her classes,” he said.

Communicating with the White House, communicating with world leaders, and communicating with NATO allies was all part of his day’s work. He said, “Communication is my toughest challenge, seeking the consensus and finding out what other people think.”

Earlier in 1991, during the first Persian Gulf War, the general oversaw the U.S. Command that kept the troops, tankers, planes and parts ready at a moment’s notice to move through Europe and Mediterranean.

In Iraq, hundreds of ethnic Kurds were dying each day as they were being more and more isolated by the late leader Saddam Hussein. Then the 10th Special Forces under Galvin’s command arrived to help with relief efforts. The tide of starvation and illness soon stemmed. The Special Forces and their medical personnel were seen by Kurdish leaders as “angels” saving lives.

In the 1991 Fourth of July parade, which the general led, were troops he commanded in the effort to aid the Kurdish refugees.

The ultimate soldier-statesman, Jack Galvin had the good fortune of seeing the Cold War end on his watch. But the developments in Europe moved so fast that even the head of NATO forces was stunned. He admitted that he could not have predicted some of the sweeping events that changed the makeup of the Eastern Bloc countries and their military forces, nor those that affected the old Soviet Union, either.

“I never expected to walk through Red Square in Moscow unless I went there as a prisoner of war. It’s tremendous, this change that we’ve seen. The changes are good for them, good for the U.S. and good for the world.”

The general was back in Wakefield in the fall of 1991 for ceremonies dedicating the then-Wakefield Junior High School in his name. In a message to students prior to the public event, Galvin’s love of history shone through, a passion he shared with his father.

“You are living in a town which is an example of American history from the time it was Lynn Village to when it became the Town of Wakefield. …As you get ready to go out in the world, the Cold War is over and the United States is the reigning super power, serving as an example of freedom, enterprise and respect for human rights.

“It’s a heavy responsibility to inherit and pick up where those before you have left off,” he said.

That day was a special one for the general, as he had a chance to talk with old friends. It was special for a couple of other reasons, too.

“History is being made here today,” said Atty. Mark Curley, the master of ceremonies and Galvin Committee member. Curley announced the establishment of the Galvin Scholars Program at the school as well as a John Rogers Galvin Scholarship through the former Wakefield Citizens’ Scholarship Foundation.

“The four stars now on the front of this building are emblems of excellence and great personal achievement. Your emblems of excellence will be through the Galvin Scholars Program,” Curley told students that day. “(General Galvin) has climbed his mountain; now you can climb your mountain.”

General Galvin stepped down as NATO commander in 1992, retiring after a 43-year military career. Then-Secretary of Defense Richard Cheney pinned the Distinguished Service Medal, First Order with oak leaf cluster, on Galvin’s uniform during the ceremony in the summer of 1992.

After his military career had ended, the lifelong student and teacher taught at West Point, Ohio State University and served as an envoy with the rank of ambassador to assist in negotiating an end to the crisis in Bosnia, part of the former Yugoslavia.

In 1995, became the sixth dean of the Fletcher School of Law and Diplomacy at Tufts University. In his reaction to the appointment, Galvin said, “I’ve always felt that the Fletcher mission is a vitally important one. That mission will grow because the world has become more inter-connected. But at the same time, the world is also more complex, more unpredictable – and so many places are potentially unstable.”

There are not enough people who are trained to articulate on the myriad questions and issues that will arise in this unpredictable geopolitical environment, he said. That is the role Galvin wanted to position the Fletcher School to fill.

Wakefield served as an important teaching tool to the general as well. As early as 1993, thanks to the General Galvin Committee made up mostly of local residents, the town hosted high-ranking Russian military leaders several times. Just a few years removed from being sworn enemies, together with their hosts, they had the chance to see small town American life first-hand, visiting places like Smith’s Drug, Hart’s Hardware, the Town Hall, the public safety buildings, the Hartshorne House and the old Colonial complex. The events began, of course, at the school named in Galvin’s honor.

The general always served. He was on a Congressional commission, for example, that essentially suggested an agency similar to the Department of Homeland Security, two years before the department was created.

In 2002, the general returned to Wakefield once again as guest lecturer of the first lecture sponsored by the Volpe Archives Committee. Not long after the attacks of Sept. 11, 2001, Galvin told those in the audience of the prospect of all-out war, “I hope to God we don’t have to do this at all. If we can get through this period using military and diplomatic power together, then we’ll have it right. … You have to go back and forth (between diplomatic and military efforts). I know that will be difficult to do after two massive buildings were destroyed in New York City.

“We have a chance to take the question of war on again but we have to use everything in our power to stay out of it without deaths and destruction. I think we can make it but we have to be firm. It may be necessary to use force at some point.”

General Galvin and his wife retired to a town outside Atlanta, Ga. in 2000, after leading the Fletcher School for five years.