Published in the May 17, 2017 edition

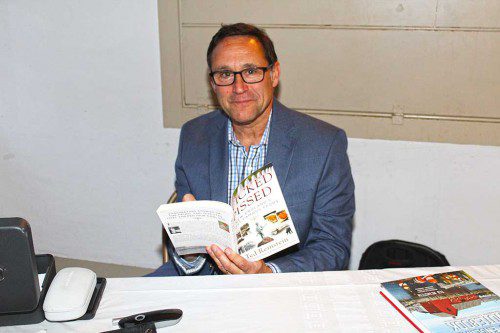

WCVB-TV Reporter Ted Reinstein discussed his book “Wicked Pissed: New England’s Most Famous Feuds” during his Author Talk presentation at the Meeting House May 11. The Friends of the Lynnfield Library sponsored the presentation. (Dan Tomasello Photo)

By DAN TOMASELLO

LYNNFIELD — People’s perceptions of who invented the airplane is not what it seems, WCVB Channel 5 reporter Ted Reinstein told two dozen attendees at the Meeting House May 11.

Reinstein appeared at the Meeting House as part of the Lynnfield Public Library’s “Author Talk” series this month, which is sponsored by the Friends of the Lynnfield Library. The “Chronicle” reporter discussed his book, “Wicked Pissed: New England’s Most Famous Feuds.”

The author previously appeared at the Meeting House last year. He said he has enjoyed his visits to Lynnfield.

“I love being in this wonderful historic building,” said Reinstein. “I love old things, but sometimes you need new things. I understand the library has persevered and perhaps there will be an opportunity to support a new library. I have been speaking at libraries for five-and-a-half years, and I always say you can tell a lot about a town by how it supports the schools and the library. I know Lynnfield will do the right thing. If you want an answer, you can Google it. If you want the right answer, ask a librarian.”

Reinstein briefly discussed some well-known New England feuds as an “appetizer” before giving an overview of the main course.

“With very little exception, people find feuds fascinating,” said Reinstein.

Reinstein recalled the feud “The Jungle Book” author Rudyard Kipling had with his brother-in-law. The feud prompted the author to “leave and never return to Vermont” even though Kipling wanted to spend the rest of his life at his home there, Naulakha.

The author noted the towns of Lexington and Concord are “still arguing to this day over which town deserves the title of birthplace of the American Revolution.”

According to Reinstein, the Battle of Bunker Hill was mostly fought at Breed’s Hill, which is why the battle’s name has been called one of “the most glaring historical errors in history.” In the 1930s, Reinstein said the Breed family was able to convince the state of Massachusetts to install a plaque acknowledging the Battle of Bunker Hill was fought on Breed’s Hill.

“Just to add insult to injury, it was installed inside the Bunker Hill Monument,” said Reinstein. “It cracks me up.”

Additionally, Reinstein noted the Bunker and Breed families are still fighting about the battle’s name on social media.

Reinstein spent the majority of the presentation discussing the feud between the Wright brothers and German immigrant Gustave Whitehead over the invention of the airplane.

“(Whitehead) may deserve credit for first flight,” said Reinstein.

Reinstein said Whitehead immigrated to the United States in 1900, and got a job designing weather balloons at the Great Blue Hill Observatory in Milton.

Whitehead later moved to Bridgeport, Connecticut, said Reinstein. After 20 failed attempts of trying to create an aircraft, which included the 20th aircraft crashing into a building in Pittsburgh, Reinstein said Whitehead’s “No. 21” took to the skies on Aug. 14, 1901. The aviator took off from a dirt road in Fairfield, Connecticut and flew over a small section of Long Island Sound. After flying for half-a-mile for just under 30 minutes, Whitehead’s two-cylinder engine aircraft landed on a vacant lot off Pine Street in Bridgeport.

After the flight, Reinstein said Whitehead “never flew again.” According to a story in the Hartford Courant by Reinstein, Whitehead “died in Bridgeport in 1927, penniless and unknown, at 57.”

The Wright Flyer was flown for 12 seconds on December 17, 1903 in Kitty Hawk, North Carolina.

Reinstein has conducted a great deal of research about Whitehead, and outlined a theory why the German aviator is not viewed as the inventor of the airplane.

“The first thing has to do with how we learn about history,” said Reinstein. “When a historical event happens, particularly a landmark achievement or an invention, contemporaries write about it in excessive detail. Fifty years out, that historical context will decrease by about 50 percent. A hundred years out, it gets reduced to the bare minimum. This is particularly significant with first flight. The Wright brothers were not alone. It was a race.”

Reinstein said Whitehead was a “poor German immigrant in a time of rising and sometimes virulent anti-German sentiment.” He said Whitehead’s flight took place in the early morning on Aug. 14, 1901 because “he didn’t want people to see what he was doing.”

Additionally, Reinstein said there are no known clear photographs of Whitehead’s No. 21 in flight, unlike the Wright Flyer. However, he said there were 30 eyewitnesses.

Reinstein said five people began examining Whitehead’s story over time, beginning with Whitehead biographer Stella Randolph in the 1940s. After the Wright Flyer was sold to the Smithsonian Institution, Reinstein said that in 1947 Connecticut made “the first of a series of official requests to conduct a forensics investigation into whether or not Gustave Whitehead might have flown.” He said the Smithsonian responded with a one-word answer.

“No,” said Reinstein. “This left a lot of people in Connecticut wondering why.”

Reinstein said the Smithsonian repeatedly denied Connecticut’s request to conduct an investigation until Congress passed the Freedom of Information Act in 1978. He said the act enabled former Connecticut Senator Lowell Weicker to take a look at the Smithsonian’s agreement with the Wright family.

According to Reinstein, Weicker determined most of the agreement was “boiler plate” except the last part of it. He said the pact stipulated that by taking the Wright Flyer, the Smithsonian agreed it was the first aircraft to take flight.

“It becomes known as the secret agreement,” said Reinstein.

Reinstein said Randolph and researcher Major William J. O’Dwyer wrote a book about the secret agreement called “History by Contract” in 1978.

“The central premise is there is a viable claim for first flight in America, and the one institution in America who could determine if this is credible will not investigate the story because they have a conflict of interest,” said Reinstein. “As you could imagine, these were not happy days for the Smithsonian. This was at the same time the Smithsonian opened the Air and Space Museum, which had the Wright Flyer as a centerpiece.”

Reinstein said teacher Andy Kosch built a replica of Whitehead’s No. 21 in the 1980s. Since Kosch did not have a pilot’s license, Reinstein said the teacher had friend and actor Cliff Robertson fly the replica.

“(Robertson) flew for just under an hour and made a perfect three point landing back in Bridgeport,” said Reinstein. “He got a hero’s welcome.”

After Robertson flew the No. 21 replica, Reinstein said “60 Minutes” aired a segment called “Wright is Wrong?”

Reinstein said aviation author and historian John Brown was hired by the Smithsonian to produce a series of television specials about the history of American aviation in 2000. During an interview with Smithsonian Aeronautics Department Senior Curator Tom Crouch, Brown asked the curator about Whitehead. Reinstein said Crouch claimed No. 21 was never flown.

After the interview, Reinstein said Brown, who was also a detective, went to Bridgeport to conduct research about Whitehead. As part of the investigation, Reinstein said Brown found a story in the Bridgeport Herald titled “Local boy flies over Long Island Sound.” Reinstein also said Brown found a blurry photograph in a museum that the historian argues is a picture of No. 21.

“The Smithsonian calls this photograph the smudge,” said Reinstein.

In March 2013, Reinstein said the publication “Jane’s All the World Aircraft” published a story stating that first flight took place in Bridgeport and not Kitty Hawk.

“That was all the state of Connecticut needed to hear,” said Reinstein. “For 100 years, they were told by the Smithsonian, North Carolina and Ohio to get lost with this cockamamie Whitehead story. The Connecticut State Assembly, without a single dissenting vote, passed a bill that makes the state of Connecticut the only state in America that recognizes someone other than the Wright brothers as the first in flight.

“Should this change history?” Reinstein aaked. “And my answer is no. My no, unlike the Smithsonian’s no, comes with a big red asterisk. The reason is this. In 1903, the Wright brothers understood that if they wanted proof that they flew, they needed a photograph of the Wright Flyer in the air. And they got one. Whitehead understood the same thing. He did everything he could do to avoid a photograph.”

While Reinstein said people’s investigations into Whitehead’s story do not change history, he said, “If you ask me if Gustave Whitehead flew before the Wrights, my answer would be yes.”

After Reinstein concluded his presentation, he was given a round of applause. He thanked the presentation’s attendees for coming to the event. He also signed copies of “Wicked Pissed” and his first book, “A New England Notebook: One Reporter, Six States, Uncommon Stories.”