A COPPER REPLICA of a Vietnam-era Marine Corps helicopter flies over Green Street in Melrose. (Terry Bleiler Photo)

By Tim Morris

On Green Street in Melrose, a weathervane rises from a garage roof. At first glance, it looks like any other weathervane you would find on a New England home or in an antique shop. It is made of copper and iron with directional letters (N, S, E, and W) jutting out from its wind-spun arms. Take a closer look, however, and you’ll notice that the weathervane at 108 Green Street is unique. It is not topped by the typical rooster, eagle, nor labrador retriever. Instead, it features a copper replica of a Sikorsky UH-34D helicopter — the same helicopter flown by United States Marine Corps pilots during the Vietnam War.

The owner of the weathervane — and the house it is connected to — is Captain Thomas Zibrofski, USMC (Retired), who piloted a UH-34D helicopter in over 200 combat missions during the Vietnam War.

A Decision of Courage and Sacrifice

On March 15, 1966, in what would be his final combat mission, Captain Zibrofski was flying to extract a patrol of Reconnaissance Marines northwest of Chu Lai, Republic of Vietnam. As he was approaching the landing zone it came under enemy fire. The leader of the Reconnaissance patrol, Marine infantry Captain James L. Compton, later wrote about the events of that day:

“As the flight reached a position about 200 meters from the zone and an altitude of 100 feet, the aircraft and the landing zone came under violent rifle and automatic weapons fire from the vicinity of the village. I informed the [helicopter pilot] flight leader of the enemy positions and intensity of fire but to my surprise he elected to land anyway.”

Despite the danger to himself, Captain Zibrofski landed and provided covering fire while his fellow Marines ran towards his aircraft. Captain Compton continued with a description of Captain Zibrofski’s aircraft in the landing zone:

“The plane [helicopter] was extremely vulnerable. As I ran toward it I could see from the dirt kicking up all around it, and that being the last aircraft left in the zone it was taking the brunt of the Viet Cong fire. The plane remained on the ground however until we could board and make certain that all the Marines were in fact clear of the area. As we lifted off, the crew chief told me that one of the pilots had been hit.”

Captain Compton concluded with the following:

“Had it not been for the courage and determination of the helicopter crew I am certain that myself and several of my men would have been killed.”

The pilot who “had been hit” was Captain Zibrofski. An enemy round struck him in the neck. Battlefield triage and multiple surgeries ultimately saved his life, but permanent damage, including damage to his voice, would remain.

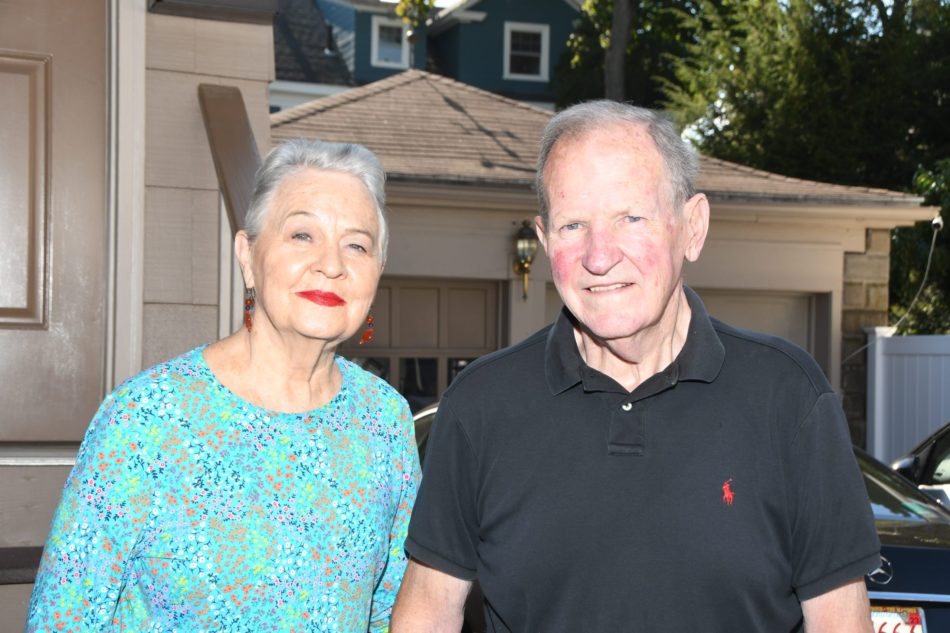

After returning to the states and retiring from the Marine Corps, Captain Zibrofski returned to work despite his handicap. He and his wife Patty settled in Melrose and raised a family on Green Street where they have lived for the past fifty years.

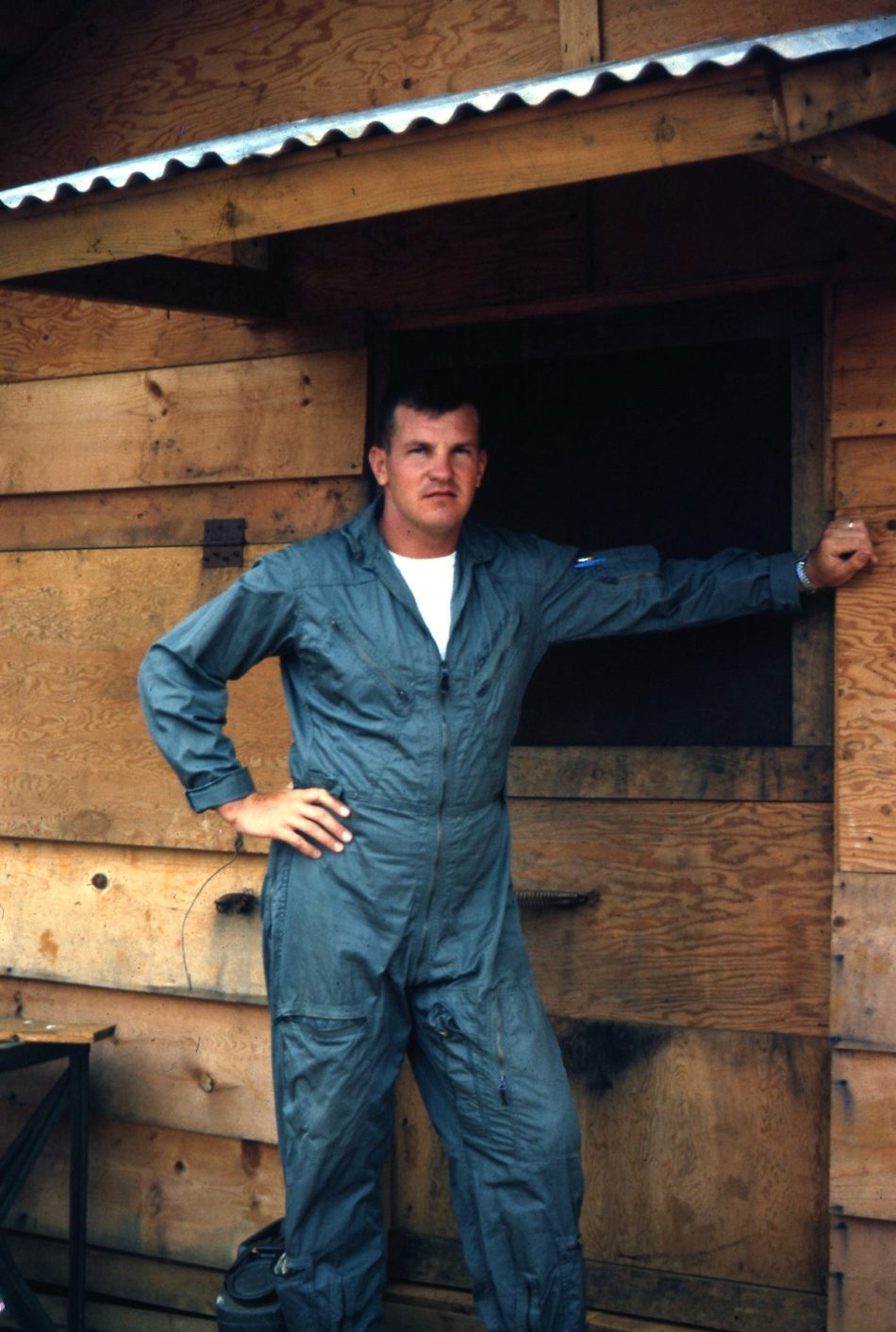

U.S. MARINE CORPS pilot Captain Thomas Zibrofski dressed in his flight suit in 1966, Da Nang, Vietnam. (Courtesy Photo)

A Personal Connection

As a child, I did not understand the significance of Tom Zibrofski’s Vietnam War service. Instead, I knew him for his other roles: backyard pool owner, friend, role model, bird-lover, car-lover. Whether by grace or accident of geography, Tom and his wife Patty have been a part of my “extended family” for decades. In the 1960s and 70s, my mother grew up on Green Street in the house next door to Tom and Patty. By the 1990s, my brothers and I had arrived, born into the same home where my mother was raised. I learned to swim next door at “Pattyandtoms” pool. In the decades since, I have counted on their presence at every birthday, graduation, backyard barbecue, and all of my adult visits home to Melrose.

It was because of this relationship that when I reached adolescence and became curious about Tom’s military service, I did not hesitate to ask him. My thirteen-year-old self spent one memorable afternoon in Tom’s basement looking at old slide-projector photographs and listening to his stories. As the projector fan whirred in the background, I remember laughing as Tom shared stories that I could picture. He explained how one of his peers brought a bowling ball to basic training (assuming incorrectly they would have time to go bowling) and was made to carry it around everywhere by the drill instructors. He told me about the competitiveness between Marine Corps and Air Force pilots, and about the South Vietnamese soldiers who would ride in his helicopter carrying three-times their body weight in equipment.

To be sure, Tom spared me from the worst of what he experienced. (He did not tell me about the day he was wounded, for example, I would read about that later). Still, I will never forget the generosity Tom showed me that day. By answering my questions Tom made me feel valued –– like he truly wanted me to understand his military service.

TOM AND PATTY Zibrofski have lived in Melrose since Tom returned from Vietnam after being wounded more than fifty years ago. (Terry Bleiler Photo)

Reaching Across a Divide

Open exchanges between veterans and non-veterans –– like the one I experienced with Tom –– are unfortunately all too rare today. Each Veterans Day, you can find articles published about the growing distance between those who served in the Armed Forces and those who didn’t — often referred to as the “civilian-military divide.” The oft-quoted statistic is that today less than 1% of the U.S. population serves in the Armed Forces, and less than 7% of the adult population are veterans. Whether or not the numbers are the cause of this so-called divide, one symptom is clear: Many adults are hesitant to ask the veterans in their lives about their military service.

The reasons for this hesitation are many. We tell ourselves that we “could never understand what they went through,” so we don’t bother asking. We worry that there may be trauma that we could “trigger” by asking a question, so we decide that we better not. We think that we don’t “have the right” to ask any questions because we didn’t serve ourselves. Better just to say “Thank you for your service” and call it a Veterans Day.

While these thoughts are understandable, they are fictional reasons for a curious person to remain silent. Instead of self-censoring, you might instead strike up a conversation with a veteran in your life. Trust that your genuine curiosity about their service will shine through in your questions. Trust that a veteran is more than capable of choosing what they will and will not share with you. You should not ask to hear about a veteran’s worst day in the military, and certainly avoid “did you kill anyone,” but you may be surprised at how well you can relate to many of their experiences.

Questions like, Who was your best friend when you served? What was the hardest part of boot camp? Do you have any funny stories from training? (Prediction: they do.) Who was your most memorable instructor? What are you most proud of from your military service? What was the weather or food like at your duty station or during your deployment? Why did you join the military? can all help you better understand someone’s service.

Contrary to what you see in movies, there are many long, often boring hours associated with military service; there are countless jokes told, deep relationships formed, and positive experiences to go along with the difficult ones. Tom Zibrofski helped my young-self realize that military service is rarely one-dimensional, even for a combat veteran. In the years since I joined the Marine Corps, I have tried to help others understand this as well. (Most recently, I spent a ruined lesson-plan indulging my U.S. History students as they asked me rapid-fire questions about my Marine Corps experience).

Captain Thomas Zibrofski, USMC (Retired) is a true war-hero who nearly lost his life while saving the lives of his fellow Marines. He is also a father, grandfather, longtime Melrose resident, and role model to many. There is no one more deserving of a heartfelt “Thank you” from his community and from his country this Veterans Day. It is worth remembering, though, that expressions of gratitude need not be limited to single-sentence exchanges. On November 11, try honoring a veteran in your life by saying more than “Thank you.” Ask them about their service. You both may be thankful that you did.