Fifty years ago, on Feb. 4, 1966, not long after his morning ritual of a Turkish bath, Lucius Beebe, syndicated columnist, journalist, photographer, gourmand, railroad historian, author, raconteur and acknowledged dandy, succumbed to a heart attack in his Hillsborough, Calif. winter home, not far from San Francisco at the age of 63. Thus came to an end the life of one of the most colorful and well-known characters in America from the 1930s through the first half of the 1960s.

Lucius Morris Beebe was not the same Lucius for whom the downtown library was named, that was his grandfather. The second Lucius was a scion of a wealthy mercantile family, born on Dec. 9, 1902. He spent his childhood at Beebe Farm overlooking Lake Quannapowitt at Beebe Cove. While the farm has been subdivided over the years, the distinctive white, wood frame house itself still majestically stands.

Throughout childhood on, young Lucius was known for his pranks, particularly at St. Mark’s School, in Southborough, and at both Yale and Harvard universities. So pronounced were some of the pranks that he was invited by the president and the dean, respectively, of each university to leave without the option to decline. Harvard eventually relented, letting him back in to complete his baccalaureate degree in 1926, only to expel him once again while he was earning his master’s degree. His most outrageous stunt? Bombing J.P. Morgan’s yacht Corsair with toilet paper from a chartered airplane, a feat all the more amazing given his loudly expressed attitude against flying later in life (in one column, he referred to a particular aircraft as a “flying cylinder of death”).

His true métier in life was writing. At Yale, he wrote regularly for The Yale Record, a campus humor magazine, also beginning his journalistic career around the same period by contributing articles to the Boston Telegram newspaper, and his career as an author by publishing several books of poetry. In 1929, Beebe went to work for the New York Herald Tribune, initially as a reporter. His first assigned story was to cover a fire one night in the city. He arrived on scene in his customary formal evening dress of top hat, tails and gloves. Likely the best dressed beat reporter of all time.

By 1934, Beebe had become nationally syndicated with his This New York column in the “Trib.” For the next 10 years, one-and-a-half million people – a telling 1 percent of the then population of the U.S. – began their day reading his column. Beebe is credited as having coined the term “café society.” In the dark years of the Great Depression, with many out of work and standing in breadlines, and World War II, Lucius Beebe wrote about, as he calculated, the five hundred people, including himself, that were sufficiently rich, famous and displaying his definition of élan as they went about at such watering holes as El Morocco, the 21 Club, the Stork Club and other like habitués. He was renowned for his florid, rococo style of writing and his “take no prisoners” attitude toward all manner of things. An example of his writing on his take on whisky:

“I recoil from the consumption of whisky which is advertised as being ‘light.’ The presumption implicit in this approach is that somehow a ‘light’ whisky is better than a ‘heavy’ whisky, but to my perverse thinking it suggests a cheap, ineffective, flavorless and underproof product that all right-minded whisky drinkers should reject.

“I want my whisky strong, boozy, potent, full bodied and of irreproachable proof, the sort that used to be consumed by heavily mustached men in cast-iron derby hats with solid gold watch chains across prosperous stomachs. Whisky for Americans ought to be the sort that eats holes in the carpet if you spill it.”

He was so widely well-known at the time that in 1937 Wolcott Gibbs wrote a two-part profile of him in The New Yorker magazine, “The Diamond Gardenia.” Lorenz Hart immortalized him in the song “Zip” in the 1940 Rodgers and Hart musical Pal Joey:

Zip! Toscanini leads the greatest of bands.

Zip! Jergens Lotion does the trick for his hands.

Zip! Rip Van Winkle on the screen should be smart.

Zip! Tyrone Power will be cast in the part.

I adore the great Confucius.

And the lines of luscious Lucius.

Wherever he went, Beebe was also known for his sartorial splendor. His wardrobe has been described as both impressive and baroque, consisting of some 40 suits, at least two mink-lined overcoats, numerous top hats and bowlers, a collection of doeskin gloves, walking sticks and a gold nugget watch chain. Much of his attire was bespoke tailoring, particularly from favorite firms in Saville Row, London. Such was his manner of dress that fellow columnist Walter Winchell dubbed him “luscious Lucius,” a soubriquet that has popped up in references ever since. He was pictured on the cover of the Jan. 16, 1939 issue of Life magazine, resplendent in full evening dress with the caption “Lucius Beebe Sets a Style.”

Lucius Beebe is also generally credited with coining the phrase “partner” when referring to individuals in a gay couple. Given the strictures and attitudes of his day, Beebe’s relationships were relatively open and well-known. In the 1930s, he was involved with society photographer Jerome Zerbe. Then in 1940, Beebe began a relationship and partnership with Charles Clegg, when both men were houseguests at the Washington, D.C. home of Hope diamond owner Evalyn Walsh McLean and which continued until Beebe’s death. Like Zerbe, Clegg was a talented photographer but with an interest in rail history, which was in line with Beebe’s abiding interest as a historian, author and photographer, himself.

When the two men decided in 1950 to decamp New York and move to Virginia City, Nev., they settled in the Piper mansion and purchased the, by then moribund, local newspaper the Territorial Enterprise, revitalizing the paper that Mark Twain had once written for. Over the period of their ownership, the two men wrote a series of historical essays for the paper called “That Was the West.”

Beebe and Clegg sold the Territorial Enterprise in 1961 and bought a winter home in Hillsborough, Calif., outside San Francisco. From this base, they continued to travel, photograph and write. Beebe wrote his final syndicated newspaper column, from 1960-1966, “This Wild West” for the San Francisco Chronicle. Over his career, he was a contributing writer to Gourmet, The New Yorker, Town and Country, Holiday, American Heritage, Playboy and Horizon.

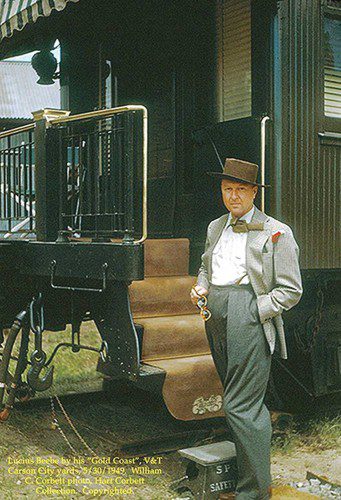

Throughout his life, Lucius Beebe only liked the very best that was available. He owned numerous Rolls Royce motorcars and two private railcars – The Gold Coast, which is currently in the collection of the California State Railway Museum, and the Virginia City. The Virginia City continues as a privately-owned railcar, fully restored to how it looked under Beebe and Clegg’s ownership and available for charter.

By the end of his life, Lucius Beebe had authored some 35 books, including many major titles on railroad history that were co-authored with Charles Clegg.

The Wakefield Daily Item published an account entitled “Lucius Morris Beebe: A Famous Son Returns” on the day of his funeral at Boston’s Emmanuel Church, Feb. 7, 1966. His ashes, reportedly along with those of two of his cherished dogs, were interred in one of the Beebe family plots at Wakefield’s Lakeside Cemetery.

Despite the passage of the years, images and writings about Lucius Beebe still surface. Most recently an online blog – steampunkvehicles.tumblr.com – has featured classic images of Beebe. The blog’s author has written about him: “Beebe considered himself a ‘connoisseur of the preposterous.’ He refused to accept a world that didn’t suit him. He had no regard for what the haters thought and he worked all the time at his art. Most importantly, he refused to give up his dignity when the rest of the world was selling it wholesale. In the sense that he was the first person out of the Victorian era to idolize it, he may just well be the first steampunk.”