Published February 19, 2021

This is the second part of a series.

By JAMES BENNETT

Melrose Historical Commission

MELROSE — They came down from Canada, returning to the country their parents had escaped, believing it had been transformed.

They sailed up from the Caribbean, hoping for something better than the exhausting heat and hard labor of the sugar plantations. Above all, they ran from the South, from the war-ravaged land that had traded the slave patrol and the overseer’s whip for the Ku Klux Klan and the heavy hand of Jim Crow. They were Melrose’s second black community, and unlike the enslaved community that preceded them, they came here voluntarily.

For a period of about a half-century following the Civil War, that community slowly grew, taking up residence in almost every neighborhood in the city, before experiencing an abrupt and marked decline. How that community managed to integrate into the city’s neighborhoods over a century ago should give people hope for a desegregated future; how those gains were so quickly lost should be a stark reminder of the enduring power and persistence of white supremacy in our community.

Post-Civil War Melrose was a world transformed. Almost no one could remember a time when enslaved people walked the streets here. Living in a whirlwind of technological and social change, a child raised in Victorian Melrose would have felt as far removed from the age of slavery as a child does today. In 1845, the railroad had come to Melrose, and every year after the train brought new families into this new town, which had finally incorporated as an independent place in 1850. In 1850, the population was 1,200; by 1900 it was over 12,000, almost all of them first-generation Melrosians. Ancient farms were broken up and parceled out for suburban developments, and the sound of house construction competed with the noise from scattered small factories. For the first time, many men, and some few women, commuted to Boston for work on a daily basis. Melrosians were investing in real estate, infrastructure, technology, and a plethora of small businesses both at home and in Boston. They were creating the suburb that we know today, living a lifestyle that had more in common with 2021 than 1841.

Black people stood among the many migrant groups who moved to Melrose in those years to join in building that prosperity. After culling through the census data from 1850 to 1940 (the most recent publicly available census), for the first time a picture of that migration has begun to take form. In 1850, the Black population of Melrose consisted of five individuals. By 1910, at the community’s height, there were 124 Black people living in Melrose, comprising about .75 percent of the city’s population. Such numbers may seem tiny, but placed in context they are significant. In that same year of 1910, the Black population of Lynn made up .8 percent of the city; in Salem it was .4 percent, in Somerville .3 percent, and even in Boston, long the center of the community, it was only 2 percent. Unlike later in the 20th century, when Black and white populations became sharply segregated, a century ago they were much more evenly dispersed. The commuter suburb was an entirely new phenomenon, and the idea that such spaces should be exclusively white domains had not yet taken hold. The belief that the presence of a single Black family could depreciate the value of a neighborhood was something that later generations would invent. The story of Melrose in these years testifies to that broad pattern.

Black families during these years found a particular welcome in the largely Irish Catholic area between Maple and West Wyoming, then known as Cork City. In the 1970s, Boston Irish Catholics would become infamous for their refusal to desegregate their schools; in the 1870s, Irish neighborhoods were the most racially integrated in Boston, and interracial marriage most frequently took place between Black people and Irish immigrants. That same cultural affinity was clearly at play in Cork City. In the early 1890s, you could say hello to Susan Ellis, up from Virginia, a single mother raising her two young daughters at 85 Baxter St.; turning left on Cutter and right on Sanford, you could doff your hat to Wesley Furlong at number 47, proud veteran of the Massachusetts 54th Regiment; taking another left, there was the Hester family at 39 Tappan, immigrants from North Carolina; at 97 Cleveland you could receive a “magnetic healing” from Eleanor Wright, an Afro-Cuban immigrant, and two doors down at 101 Cleveland St., Moses Mitchell would talk your ear off about politics.

Moses Mitchell was, like Furlong, a veteran of the Civil War, having served in the 5th Massachusetts Cavalry Regiment, the only Black cavalry unit from Massachusetts formed during the war. He had fought at the Siege of Petersburg, and this experience became an important part of his identity, as his headstone at Wyoming Cemetery is inscribed “5th Mass. Vol. Cav. Comrade at Rest.” Since he worked as a stonemason, he might have carved the stone himself. Mitchell was himself a Northerner, having been born in Marshfield, but the experience of freeing his brethren in the South had clearly inspired him to assert his own right to participate in government. Mitchell was an active member of the Democratic Party, an unusual affiliation at a time when the Republican Party commanded near universal loyalty from Black voters. He was elected the party’s Committee Member for Melrose at least twice, in 1882 and 1884. In 1884 he addressed the party’s nominating convention. The Boston Globe reported: “A black man, Mr. M. P. Mitchell of Melrose, a member of the district committee, called the delegates to order at 2:20 o’clock, greeted with applause as he took the chair. He pleaded for harmony and wisdom in the deliberations before them…. He denounced the recent record of the Republican party and its tendencies in monopoly…. When he declared that “the honest people of the Sixth District will put down both Henry Cabot Lodge and his purse,” the air was rent with shouts.” In 1884, it was possible for a Black Melrose man like Mitchell to be elected by his white neighbors to act as their sole representative in party politics, and to receive acclaim for his oratory and leadership. That possibility has not been realized since.

Black people were not just moving into Cork City. A number of Black families would make their homes in the emerging Protestant neighborhood centered around the Melrose Common, particularly on the upper reaches of Laurel Street and its surrounds. In the 1910s, you would have found William and Mary Harvey, from Virginia and North Carolina, raising their family at 185 Laurel, and next door at 183 Laurel was the Smith family, with parents Samuel and Anna from Virginia and Mississippi; around the corner at 416 Grove were George and Mary Sampson, raising their eight children, and next door at 418 was the Joseph family, with father George hailing from the West Indies. While these families lived in close proximity, there is little evidence of the later practice of blockbusting in the neighborhood, as other East Side Black families during these years found homes further down Laurel, on Beech Avenue (then known as Folsom Street), on Waverly Avenue, and what became Slayton Road. The East Side in the first decade of the twentieth century was arguably more open to homeownership by Black residents than it was to Catholics.

A large number of Black residents also found homes along Main Street and its surrounding courts and alleys (long since demolished for parking) especially single people and couples looking to rent apartments. Thus, for example, we find Mary Ransom, by profession a “matron” living above 545 Main St. (the Affairs to Remember building), along with her young relative Violet, who worked as a governess. A block up Main from Ransom’s address, between the Methodist Church and East Emerson, stood the Black enclave of Ingalls Court. Nowadays this address is occupied by an office building, but from 1900 to 1920 it was home to four residences that were exclusively populated by Black immigrants from the South, making it the only all-Black residential street in Melrose’s history. Like many of Melrose’s Black newcomers, the people of Ingalls Court were laborers, performing grueling, unskilled work. But the Melrose housing market had enough range that they could afford to rent homes just off of Main Street, perhaps hoping to save up enough money to one day join the Black homeowners in Cork City or the East Side. For those who could not afford the rent on Main Street, there was always the area around Swains Pond, which was a veritable no-man’s land at the time, home to a number of squatter residences, some of them Black.

There were some Melrose neighborhoods which were beyond the financial capabilities of Black homeowners in turn-of-the-century Melrose, but some Black men and women made their homes there as domestic servants, placing Black people in every corner of the city. In the census of 1870, three young Black migrants fleeing post-war Virginia could take in views of Ell Pond while enjoying the new-found feeling of being compensated for their work: Lettie Miles, who worked for A.V. Lynde at 39 Lake Avenue, Violet Jarvis, who worked for George Emerson at 17-19 Lake Avenue, and Martha James, who worked for Mary Livermore at 21 W Emerson Street. Emerson and Livermore had been abolitionists before the war, and their hiring of Black labor may have been an extension of their pre-war commitment to improving Black lives. Melrose was quickly becoming a city of big, rambling Queen Anne houses that required constant care and maintenance, and Black people filled many of those roles, particularly in homes on and just off of Franklin Street in the Highlands, and on both East and West Emerson Streets.

Thanks to the box marked “race” on U.S. Census forms, Black residence in the city is easy to track; Black business ownership has proven more elusive to discover, especially given the ephemeral nature of most small businesses. Nonetheless, there is evidence to suggest that there was at least some Black participation in the Melrose small business community. After living at 94 Rowe St. for over 20 years, around 1930 George Birmingham rented space for an upholstery shop next to the YMCA building at 4 East Foster St. when he was in his late 70s. In 1910, William Honsucle, a migrant from South Carolina living at 511 Main St. (long since demolished, now Starbucks) who usually worked as a janitor, opened up a short-lived restaurant in his home. In 1900, Virginia Jefferson ran a boarding house at 34 Essex St. with three young tenants who, like her, were migrants from Virginia. Further research may well uncover more such examples.

None of this racial integration would have been possible were it not for white tolerance of Black presence in the city—but the nature of this “tolerance” should in no way be overstated. At that time, the most popular entertainment in Melrose by far was minstrelsy. Every year, the Melrose Athletic Club’s biggest fundraiser was their annual minstrel show, which featured members of the Board of Aldermen and other respected locals caking their faces with black paint and singing and dancing in an outrageously demeaning caricature of Black people. The minstrel tradition was a uniting bond for white people across the city. In 1899, perhaps in a nod to the suffrage movement, the highly progressive Unitarian Church of Melrose presented an all-woman minstrel show. In 1906, perhaps to cast off the stereotype of the Irish drunkard, the St. Mary’s Catholic Temperance Society mounted a minstrel show at City Hall. Whether an Italian saying a Novena at St. Mary’s, a Jew reciting the Torah at the Hebrew School on Grove Street, or an old Yankee attending Sunday School at the Methodist Church, most white people in the city could put aside their significant differences to feel a shared superiority over the Black families of Melrose.

And yet, unlike in future decades, Black people were willingly accorded a place in the community. Perhaps nothing bears up that fact better than a series of advertisements taken out in the Boston newspapers in the late 1890s by the white real estate agent Minnie Farnsworth, who lived at 60 Upham Street. In 1897, for example, she sponsored this ad in the Boston Herald:

“GOOD PLACE FOR COLORED FOLKS—$20 cash and $20 monthly buys a 2-story house. 8 rooms and attic. Spot pond water, water closet, furnace, cemented cellar, over 6000 ft. land, fruit, henhouse, &c.; nice location and neighborhood. 5 minutes to depot; price $2300. FARNSWORTH. 634 Main St., opp. Methodist Church, Melrose; houses to rent.”

Over a century ago, at least one real estate agent in Melrose was not trying to keep Black people out; she was trying to convince them to move in. In this jostling, dizzying world around the year 1900, many Melrosians imagined this suburb not as a lily-white place isolated from the wider tapestry of American life, but as an integral part of that warp and weft, with Black people making up some of those binding strands.

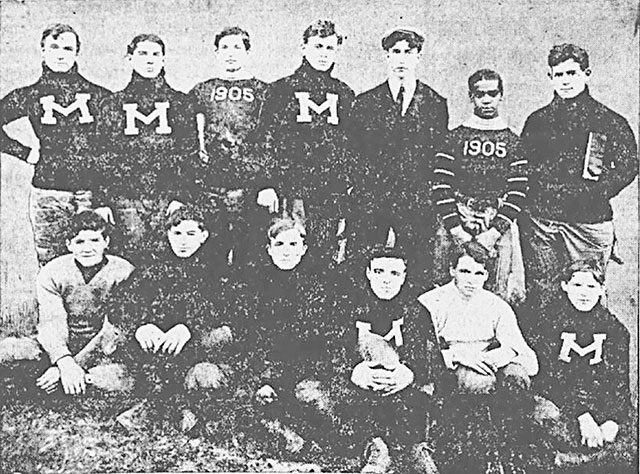

Casting back to this period in Melrose’s Black history, I think of the photograph of Robert Gould Shaw Furlong, Melrose High Class of 1905, in his football uniform with his teammates, staring out at us across the divide of a century. As the only Black boy on the team, he clearly stands out. Yet he was part of the team. He knew other Black children in his own neighborhood and elsewhere in the city; sometimes their parents rented their homes, but just as often they owned them. His father was highly respected by Black and white people alike around town. Around the corner had lived Moses Mitchell, now departed, but well remembered as the head of the town’s Democrats. On Main Street he could pass by Black people working in the commercial district’s businesses, and in a few cases owning them. With the local real estate market wide open, there was every sign that more Black people would continue to move into the city. Despite the constant insult of the minstrel shows, the future of Black Melrose seemed bright.

As we shall see in our next installment, the power of white supremacy proved stronger—at least for a time.

The author invites readers to visit the social media pages of the Melrose Historical Commission, including Facebook and Instagram, where they can find supplementary images and text related to this story. They can also explore an interactive map of people of color in Melrose history during this period at https://www.google.com/maps/d/edit?mid=1VhzZB6I89NacVwdUYGQc6kzb3PMSjcej&usp=sharing.