Published January 20, 2021

By HELEN BREEN

John Adams, our second president, and his eldest son, John Quincy Adams, our sixth president, both quietly departed Washington on the eve of their opponent’s inauguration.

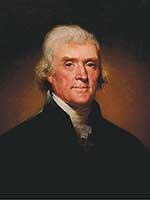

Each did so in good conscience, leaving their successors, Thomas Jefferson and Andrew Jackson respectively, to enjoy two terms in office.

The election of 1800

Our Founding Fathers John Adams (1735-1826) and Thomas Jefferson (1743-1826) had worked harmoniously together in the early days of the republic. Jefferson had been an intimate of the Adams family during their diplomatic service in Europe. Yet, the relationship between these two patriots had eroded during Adams’ tenure as our second president when Jefferson served as his vice president.

In 1800, Jefferson challenged Adams’ bid for a second term. Presidential candidates in those days stayed home and did not campaign actively. The fight was carried on by surrogates, mostly in the press. Federalists, led by Adams, attacked Jefferson as “an un-Christian deist” who sympathized with the cause of the French Revolution. Republicans, the party of Jefferson, raged against Adams’ purported Anglophile inclinations and his support of strong federal powers.

The mudslinging became unrelenting. Adams was labeled “a fool, a hypocrite, a criminal and a tyrant.” Jefferson was branded “a weakling, a libertine and a coward.” Adams supporters called Jefferson “a low-lived fellow, son of a half-breed Indian squaw, sired by a Virginia mulatto father.”

The ethereal Jefferson hired a hatchet man named James Callendar to do his smearing. The latter was largely successful in persuading the electorate that Adams was itching to attack France. The ploy worked and Adams lost. The duplicitous Callendar would later betray Jefferson by exposing his relationship with Sally Hemings.

Inauguration Day

On the early morning of Inauguration Day, March 4, 1801, John Adams slipped out of town in a public stagecoach, heading for Baltimore and the long trip home. His wife, Abigail, had preceded him to Quincy. Weighing heavily on them both was the recent death of their son Charles from alcoholism a few months prior.

John Adams later remarked that he “put little stock in ceremonies,” recalling that no family members had been present when he took the same oath in 1797. Meanwhile, back in Washington, Jefferson had called for reconciliation in his address declaring, “We are all Republicans, we are all Federalists.”

Retirement

Leaving political turmoil behind, John Adams faced retirement with a degree of serenity. His eldest son, John Quincy, had reassured him, “You were the man, not of any party, but of the whole nation.” While Abigail tended to the challenging matters of her children and extended family, John took solace in reading, letter writing and beginning his memoir. That task, however, was not completed as he preferred working the soil on his beloved Quincy farm. He told his sons with satisfaction “nothing remains between me and my grave but my plough.”

Toward the end of their lives, Adams and Jefferson resumed their correspondence. In addition to family and domestic matters, the two elderly statesmen exchanged views on politics, religion, literature, the classics and contemporary affairs. Each avoided subjects painful to the other, particularly the looming dilemma of slavery. Some 158 of their letters were preserved for posterity.

Both men had put their political differences behind them. Adams and Jefferson died on the same day, July 4, 1826, the 50th anniversary of the signing of the Declaration of Independence. The nation interpreted this event as evidence of divine favor.

The election 1828

John Quincy Adams’ (1767-1848) singular term as president bore many similarities to that of his father’s. His opponent was his former political ally Andrew Jackson (1767-1845). Adams had defeated Jackson in the contested presidential election of 1824, leaving lasting scars on the electorate. Jackson’s populist views had gained increasing acceptance with the expansion of the West. John Adams had warned his son that he must be prepared for “defeat by public misunderstanding and ingratitude.”

John Quincy attempted cordial relations with the incoming president, though to little avail. He offered use of the White House for pre-inaugural festivities, but Jackson declined the proposal. Some 10,000 raucous supporters gathered in Washington for “Old Hickory’s” triumphant arrival. JQA’s absence at the inauguration was hardly noticed.

Family matters

John Quincy’s political defeat, however, paled in the light of personal anguish. Like his father before him, JQA’s diplomatic career in his youth had occasioned lengthy absences from his young family.

In 1809, Adams was appointed ambassador to Russia, an assignment that lasted six years. He and his wife Louisa Catherine left their two older sons, 8-year-old George and 6-year-old John, in the care of his aging parents, setting them on a collision course with tragedy from an early age. The toddler Charles Francis accompanied his parents abroad, a circumstance that provided him a psychological and moral advantage in life.

Concerned about his eldest son’s drinking and errant ways, John Quincy admonished George to embrace “unsullied temperance.” Years later when JQA and Louisa summoned their ill-fated son to Washington to aid in their move back to Quincy, the young man was undone. While the circumstances are unclear, George Adams boarded a steamboat in Providence on April 29, 1829 and disappeared overboard in the middle of the night. The tragedy left John Quincy “unhinged by grief and guilt.”

Their youngest son Charles Francis was left to sort out the details of George’s sad legacy, including gambling debts and an illegitimate child. His brother John would succumb within a few years.

Served in Congress

Retirement in Quincy did not suit JQA as it had his father. In 1830, he won a seat in the U.S. House of Representatives, where he served Massachusetts for 17 years, the only former president to do so. John Quincy flourished in this new setting, becoming a vocal supporter in the anti-slavery movement.

He also helped establish the Smithsonian Institution dedicated to the study of science and art in America. According to one historian, Adams, “a fearless debater, was more successful in his causes in Congress than he had been at the White House.”

After a period of declining health, John Quincy, at age 80, suffered a stroke on the House floor and died there two days later. Following a massive state funeral, his body was laid to rest in Quincy.

His last words were, “This is the end of the earth, but I am composed.”

Reflections

John Adams and his son John Quincy both experienced the humiliation and disappointment of a one-term presidency. Their opponents, Thomas Jefferson and Andrew Jackson, each represented conflicting political views as the new nation was expanding and defining itself in the early 19th century.

Both Adams men accepted their loss and then lived the rest of their lives with dignity and purpose.

The fact that neither attended the inauguration of his successor became a tiny footnote in American history.

— Send comments to helenbreen@comcast.net.